Many producers do not sell products or services directly to consumers and instead use marketing intermediaries to execute an assortment of necessary functions to get the product to the final user. These intermediaries, such as middlemen (wholesalers, retailers, agents, and brokers), distributors, or financial intermediaries, typically enter into longer-term commitments with the producer and make up what is known as the marketing channel, or the channel of distribution. Manufacturers use raw materials to produce finished products, which in turn may be sent directly to the retailer, or, less often, to the consumer. However, as a general rule, finished goods flow from the manufacturer to one or more wholesalers before they reach the retailer and, finally, the consumer. Each party in the distribution channel usually acquires legal possession of goods during their physical transfer, but this is not always the case. For instance, in consignment selling, the producer retains full legal ownership even though the goods may be in the hands of the wholesaler or retailer—that is, until the merchandise reaches the final user or consumer.

Channels of distribution tend to be more direct—that is, shorter and simpler—in the less industrialized nations. There are notable exceptions, however. For instance, the Ghana Cocoa Marketing Board collects cacao beans in Ghana and licenses trading firms to process the commodity. Similar marketing processes are used in other West African nations. Because of the vast number of small-scale producers, these agents operate through middlemen who, in turn, enlist sub-buyers to find runners to transport the products from remote areas. Japan's marketing organization was, until the late 20th century, characterized by long and complex channels of distribution and a variety of wholesalers. It was possible for a product to pass through a minimum of five separate wholesalers before it reached a retailer.

Companies have a wide range of distribution channels available to them, and structuring the right channel may be one of the company's most critical marketing decisions. Businesses may sell products directly to the final customer, as Land's End, Inc., does with its mail-order goods and as is the case with most industrial capital goods. Or they may use one or more intermediaries to move their goods to the final user. The design and structure of consumer marketing channels and industrial marketing channels can be quite similar or vary widely.

The channel design is based on the level of service desired by the target consumer. There are five primary service components that facilitate the marketer's understanding of what, where, why, when, and how target customers buy certain products. The service variables are quantity or lot size (the number of units a customer purchases on any given purchase occasion), waiting time (the amount of time customers are willing to wait for receipt of goods), proximity or spatial convenience (accessibility of the product), product variety (the breadth of assortment of the product offering), and service backup (add-on services such as delivery or installation provided by the channel). It is essential for the designer of the marketing channel—typically the manufacturer—to recognize the level of each service point that the target customer desires. A single manufacturer may service several target customer groups through separate channels, and therefore each set of service outputs for these groups could vary. One group of target customers may want elevated levels of service (that is, fast delivery, high product availability, large product assortment, and installation). Their demand for such increased service translates into higher costs for the channel and higher prices for customers. However, the prosperity of discount and warehouse stores demonstrates that customers are willing to accept lower service outputs if this leads to lower prices.

Many producers do not sell products or services directly to consumers and instead use marketing intermediaries to execute an assortment of necessary functions to get the product to the final user. These intermediaries, such as middlemen (wholesalers, retailers, agents, and brokers), distributors, or financial intermediaries, typically enter into longer-term commitments with the producer and make up what is known as the marketing channel, or the channel of distribution. Manufacturers use raw materials to produce finished products, which in turn may be sent directly to the retailer, or, less often, to the consumer. However, as a general rule, finished goods flow from the manufacturer to one or more wholesalers before they reach the retailer and, finally, the consumer. Each party in the distribution channel usually acquires legal possession of goods during their physical transfer, but this is not always the case. For instance, in consignment selling, the producer retains full legal ownership even though the goods may be in the hands of the wholesaler or retailer—that is, until the merchandise reaches the final user or consumer.

Channels of distribution tend to be more direct—that is, shorter and simpler—in the less industrialized nations. There are notable exceptions, however. For instance, the Ghana Cocoa Marketing Board collects cacao beans in Ghana and licenses trading firms to process the commodity. Similar marketing processes are used in other West African nations. Because of the vast number of small-scale producers, these agents operate through middlemen who, in turn, enlist sub-buyers to find runners to transport the products from remote areas. Japan's marketing organization was, until the late 20th century, characterized by long and complex channels of distribution and a variety of wholesalers. It was possible for a product to pass through a minimum of five separate wholesalers before it reached a retailer.

Companies have a wide range of distribution channels available to them, and structuring the right channel may be one of the company's most critical marketing decisions. Businesses may sell products directly to the final customer, as Land's End, Inc., does with its mail-order goods and as is the case with most industrial capital goods. Or they may use one or more intermediaries to move their goods to the final user. The design and structure of consumer marketing channels and industrial marketing channels can be quite similar or vary widely.

The channel design is based on the level of service desired by the target consumer. There are five primary service components that facilitate the marketer's understanding of what, where, why, when, and how target customers buy certain products. The service variables are quantity or lot size (the number of units a customer purchases on any given purchase occasion), waiting time (the amount of time customers are willing to wait for receipt of goods), proximity or spatial convenience (accessibility of the product), product variety (the breadth of assortment of the product offering), and service backup (add-on services such as delivery or installation provided by the channel). It is essential for the designer of the marketing channel—typically the manufacturer—to recognize the level of each service point that the target customer desires. A single manufacturer may service several target customer groups through separate channels, and therefore each set of service outputs for these groups could vary. One group of target customers may want elevated levels of service (that is, fast delivery, high product availability, large product assortment, and installation). Their demand for such increased service translates into higher costs for the channel and higher prices for customers. However, the prosperity of discount and warehouse stores demonstrates that customers are willing to accept lower service outputs if this leads to lower prices.

Channel functions and flows

In order to deliver the optimal level of service outputs to their target consumers, manufacturers are willing to allocate some of their tasks, or marketing flows, to intermediaries. As any marketing channel moves goods from producers to consumers, the marketing intermediaries perform, or participate in, a number of marketing flows, or activities. The typical marketing flows, listed in the usual sequence in which they arise, are collection and distribution of marketing research information (information), development and dissemination of persuasive communications (promotion), agreement on terms for transfer of ownership or possession (negotiation), intentions to buy (ordering), acquisition and allocation of funds (financing), assumption of risks (risk taking), storage and movement of product (physical possession), buyers paying sellers (payment), and transfer of ownership (title).

Each of these flows must be performed by a marketing intermediary for any channel to deliver the goods to the final consumer. Thus, each producer must decide who will perform which of these functions in order to deliver the service output levels that the target consumers desire. Producers delegate these flows for a variety of reasons. First, they may lack the financial resources to carry out the intermediary activities themselves. Second, many producers can earn a superior return on their capital by investing profits back into their core business rather than into the distribution of their products. Finally, intermediaries, or middlemen, offer superior efficiency in making goods and services widely available and accessible to final users. For instance, in overseas markets it may be difficult for an exporter to establish contact with end users, and various kinds of agents must therefore be employed. Because an intermediary typically focuses on only a small handful of specialized tasks within the marketing channel, each intermediary, through specialization, experience, or scale of operation, can offer a producer greater distribution benefits.

Factors influencing business customers

Although business customers are affected by the same cultural, social, personal, and psychological factors that influence consumer customers, the business arena imposes other factors that can be even more influential. First, there is the economic environment, which is characterized by such factors as primary demand, economic forecast, political and regulatory developments, and the type of competition in the market. In a highly competitive market such as airline travel, firms may be concerned about price and therefore make purchases with a focus on saving money. In markets where there is more differentiation among competitors—e.g., in the hotel industry—many firms may make purchases with a focus on quality rather than on price.

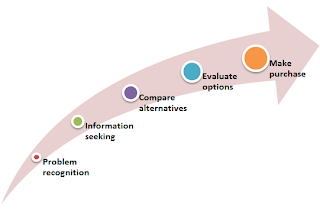

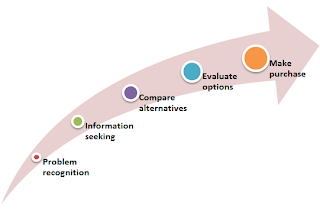

A consumer's buying task is affected significantly by the level of purchase involvement. The level of involvement describes how important the decision is to the consumer; high involvement is usually associated with purchases that are expensive, infrequent, or risky. Buying also is affected by the degree of difference between brands in the product category. The buying task can be grouped into four categories based on whether involvement is high or low and whether brand differences are great or small.

High-involvement purchases

Complex buying behaviour occurs when the consumer is highly involved with the purchase and when there are significant differences between brands. This behaviour can be associated with the purchase of a new home or of an advanced computer. Such tasks are complex because the risk is high (significant financial commitment), and the large differences among brands or products require gathering a substantial amount of information prior to purchase. Marketers who wish to influence this buying task must help the consumer process the information as readily as possible. This may include informing the consumer about the product category and its important attributes, providing detailed information about product benefits, and motivating sales personnel to influence final brand choice. For instance, realtors may offer consumers a book or a video featuring photographs and descriptions of each available home. And a computer salesperson is likely to spend time in the retail store providing information to customers who have questions.

Dissonance-reducing buying behaviour occurs when the consumer is highly involved but sees little difference between brands. This is likely to be the case with the purchase of a lawn mower or a diamond ring. After making a purchase under such circumstances, a consumer is likely to experience the dissonance that comes from noticing that other brands would have been just as good, if not slightly better, in some dimensions. A consumer in such a buying situation will seek information or ideas that justify the original purchase.

Low-involvement purchases

There are two types of low-involvement purchases. Habitual buying behaviour occurs when involvement is low and differences between brands are small. Consumers in this case usually do not form a strong attitude toward a brand but select it because it is familiar. In these markets, promotions tend to be simple and repetitive so that the consumer can, without much effort, learn the association between a brand and a product class. Marketers may also try to make their product more involving. For instance, toothpaste was at one time purchased primarily out of habit, but Proctor and Gamble Co. introduced a brand, Crest toothpaste, that increased consumer involvement by raising awareness about the importance of good dental hygiene.

Brand differences

Variety-seeking buying behaviour occurs when the consumer is not involved with the purchase, yet there are significant brand differences. In this case, the cost of switching products is low, and so the consumer may, perhaps simply out of boredom, move from one brand to another. Such is often the case with frozen desserts, breakfast cereals, and soft drinks. Dominant firms in such a market situation will attempt to encourage habitual buying and will try to keep other brands from being considered by the consumer. These strategies reduce customer switching behaviour. Challenger firms, on the other hand, want consumers to switch from the market leader, so they will offer promotions, free samples, and advertising that encourage consumers to try something new.

Variety-seeking buying behaviour occurs when the consumer is not involved with the purchase, yet there are significant brand differences. In this case, the cost of switching products is low, and so the consumer may, perhaps simply out of boredom, move from one brand to another. Such is often the case with frozen desserts, breakfast cereals, and soft drinks. Dominant firms in such a market situation will attempt to encourage habitual buying and will try to keep other brands from being considered by the consumer. These strategies reduce customer switching behaviour. Challenger firms, on the other hand, want consumers to switch from the market leader, so they will offer promotions, free samples, and advertising that encourage consumers to try something new.

Factors influencing consumers

Four major types of factors influence consumer buying behaviour: cultural, social, personal, and psychological.

Cultural factors

Cultural factors have the broadest influence, because they constitute a stable set of values, perceptions, preferences, and behaviours that have been learned by the consumer throughout life. For example, in Western cultures consumption is often driven by a consumer's need to express individuality, while in Eastern cultures consumers are more interested in conforming to group norms. In addition to the influence of a dominant culture, consumers may also be influenced by several subcultures. In Quebec the dominant culture is French-speaking, but one influential subculture is English-speaking. Social class is also a subcultural factor: members of any given social class tend to share similar values, interests, and behaviours.

Social factors

A consumer may interact with several individuals on a daily basis, and the influence of these people constitutes the social factors that impact the buying process. Social factors include reference groups—that is, the formal or informal social groups against which consumers compare themselves. Consumers may be influenced not only by their own membership groups but also by reference groups of which they wish to be a part. Thus, a consumer who wishes to be considered a successful white-collar professional may buy a particular kind of clothing because the people in this reference group tend to wear that style. Typically, the most influential reference group is the family. In this case, family includes the people who raised the consumer (the “family of orientation”) as well as the consumer's spouse and children (the “family of procreation”). Within each group, a consumer will be expected to play a specific role or set of roles dictated by the norms of the group. Roles in each group generally are tied closely to status.

Personal factors

Personal factors include individual characteristics that, when taken in aggregate, distinguish the individual from others of the same social group and culture. These include age, life-cycle stage, occupation, economic circumstances, and lifestyle. A consumer's personality and self-conception will also influence his or her buying behaviour.

Psychological factors

Finally, psychological factors are the ways in which human thinking and thought patterns influence buying decisions. Consumers are influenced, for example, by their motivation to fulfill a need. In addition, the ways in which an individual acquires and retains information will affect the buying process significantly. Consumers also make their decisions based on past experiences—both positive and negative.

Marketing evaluation and control

No marketing process, even the most carefully developed, is guaranteed to result in maximum benefit for a company. In addition, because every market is changing constantly, a strategy that is effective today may not be effective in the future. It is important to evaluate a marketing program periodically to be sure that it is achieving its objectives.

Marketing control

There are four types of marketing control, each of which has a different purpose: annual-plan control, profitability control, efficiency control, and strategic control.

Annual-plan control

The basis of annual-plan control is managerial objectives—that is to say, specific goals, such as sales and profitability, that are established on a monthly or quarterly basis. Organizations use five tools to monitor plan performance. The first is sales analysis, in which sales goals are compared with actual sales and discrepancies are explained or accounted for. A second tool is market-share analysis, which compares a company's sales with those of its competitors. Companies can express their market share in a number of ways, by comparing their own sales to total market sales, sales within the market segment, or sales of the segment's top competitors. Third, marketing expense-to-sales analysis gauges how much a company spends to achieve its sales goals. The ratio of marketing expenses to sales is expected to fluctuate, and companies usually establish an acceptable range for this ratio. In contrast, financial analysis estimates such expenses (along with others) from a corporate perspective. This includes a comparison of profits to sales (profit margin), sales to assets (asset turnover), profits to assets (return on assets), assets to worth (financial leverage), and, finally, profits to worth (return on net worth). Finally, companies measure customer satisfaction as a means of tracking goal achievement. Analyses of this kind are generally less quantitative than those described above and may include complaint and suggestion systems, customer satisfaction surveys, and careful analysis of reasons why customers switch to a competitor's product.

The basis of annual-plan control is managerial objectives—that is to say, specific goals, such as sales and profitability, that are established on a monthly or quarterly basis. Organizations use five tools to monitor plan performance. The first is sales analysis, in which sales goals are compared with actual sales and discrepancies are explained or accounted for. A second tool is market-share analysis, which compares a company's sales with those of its competitors. Companies can express their market share in a number of ways, by comparing their own sales to total market sales, sales within the market segment, or sales of the segment's top competitors. Third, marketing expense-to-sales analysis gauges how much a company spends to achieve its sales goals. The ratio of marketing expenses to sales is expected to fluctuate, and companies usually establish an acceptable range for this ratio. In contrast, financial analysis estimates such expenses (along with others) from a corporate perspective. This includes a comparison of profits to sales (profit margin), sales to assets (asset turnover), profits to assets (return on assets), assets to worth (financial leverage), and, finally, profits to worth (return on net worth). Finally, companies measure customer satisfaction as a means of tracking goal achievement. Analyses of this kind are generally less quantitative than those described above and may include complaint and suggestion systems, customer satisfaction surveys, and careful analysis of reasons why customers switch to a competitor's product.

Profitability control

Profitability control and efficiency control allow a company to closely monitor its sales, profits, and expenditures. Profitability control demonstrates the relative profit-earning capacity of a company's different products and consumer groups. Companies are frequently surprised to find that a small percentage of their products and customers contribute to a large percentage of their profits. This knowledge helps a company allocate its resources and effort.

Efficiency control

Efficiency control involves micro-level analysis of the various elements of the marketing mix, including sales force, advertising, sales promotion, and distribution. For example, to understand its sales-force efficiency, a company may keep track of how many sales calls a representative makes each day, how long each call lasts, and how much each call costs and generates in revenue. This type of analysis highlights areas in which companies can manage their marketing efforts in a more productive and cost-effective manner.

Strategic control

Strategic control processes allow managers to evaluate a company's marketing program from a critical long-term perspective. This involves a detailed and objective analysis of a company's organization and its ability to maximize its strengths and market opportunities. Companies can use two types of strategic control tools. The first, which a company uses to evaluate itself, is called a marketing-effectiveness rating review. In order to rate its own marketing effectiveness, a company examines its customer philosophy, the adequacy of its marketing information, and the efficiency of its marketing operations. It will also closely evaluate the strength of its marketing strategy and the integration of its marketing tactics.

Having developed a strategy, a company must then decide which tactics will be most effective in achieving strategy goals. Tactical marketing involves creating a marketing mix of four components—product, price, place, promotion—that fulfills the strategy for the targeted set of customer needs.

Product

Product development

The first marketing-mix element is the product, which refers to the offering or group of offerings that will be made available to customers. In the case of a physical product, such as a car, a company will gather information about the features and benefits desired by a target market. Before assembling a product, the marketer's role is to communicate customer desires to the engineers who design the product or service. This is in contrast to past practice, when engineers designed a product based on their own preferences, interests, or expertise and then expected marketers to find as many customers as possible to buy this product. Contemporary thinking calls for products to be designed based on customer input and not solely on engineers' ideas.

In traditional economies, the goods produced and consumed often remain the same from one generation to the next—including food, clothing, and housing. As economies develop, the range of products available tends to expand, and the products themselves change. In contemporary industrialized societies, products, like people, go through life cycles: birth, growth, maturity, and decline. This constant replacement of existing products with new or altered products has significant consequences for professional marketers. The development of new products involves all aspects of a business—production, finance, research and development, and even personnel administration and public relations.

Packaging and branding

Marketing a service product

The same general marketing approach about the product applies to the development of service offerings as well. For example, a health maintenance organization (HMO) must design a contract for its members that describes which medical procedures will be covered, how much physician choice will be available, how out-of-town medical costs will be handled, and so forth. In creating a successful service mix, the HMO must choose features that are preferred and expected by target customers, or the service will not be valued in the marketplace.

The same general marketing approach about the product applies to the development of service offerings as well. For example, a health maintenance organization (HMO) must design a contract for its members that describes which medical procedures will be covered, how much physician choice will be available, how out-of-town medical costs will be handled, and so forth. In creating a successful service mix, the HMO must choose features that are preferred and expected by target customers, or the service will not be valued in the marketplace.

Price

Place

Promotion

Promotion, the fourth marketing-mix element, consists of several methods of communicating with and influencing customers. The major tools are sales force, advertising, sales promotion, and public relations.

Sales force

Sales representatives are the most expensive means of promotion, because they require income, expenses, and supplementary benefits. Their ability to personalize the promotion process makes salespeople most effective at selling complex goods, big-ticket items, and highly personal goods—for example, those related to religion or insurance. Salespeople are trained to make presentations, answer objections, gain commitments to purchase, and manage account growth. Some companies have successfully reduced their sales-force costs by replacing certain functions (for example, finding new customers) with less expensive methods (such as direct mail and telemarketing).

Sales representatives are the most expensive means of promotion, because they require income, expenses, and supplementary benefits. Their ability to personalize the promotion process makes salespeople most effective at selling complex goods, big-ticket items, and highly personal goods—for example, those related to religion or insurance. Salespeople are trained to make presentations, answer objections, gain commitments to purchase, and manage account growth. Some companies have successfully reduced their sales-force costs by replacing certain functions (for example, finding new customers) with less expensive methods (such as direct mail and telemarketing).

Advertising

Advertising includes all forms of paid, nonpersonal communication and promotion of products, services, or ideas by a specified sponsor. Advertising appears in such media as print (newspapers, magazines, billboards, flyers) or broadcast (radio, television). Print advertisements typically consist of a picture, a headline, information about the product, and occasionally a response coupon. Broadcast advertisements consist of an audio or video narrative that can range from short 15-second spots to longer segments known as infomercials, which generally last 30 or 60 minutes.

Sales promotion

Public relations

Public relations, in contrast to advertising and sales promotion, generally involves less commercialized modes of communication. Its primary purpose is to disseminate information and opinion to groups and individuals who have an actual or potential impact on a company's ability to achieve its objectives. In addition, public relations specialists are responsible for monitoring these individuals and groups and for maintaining good relationships with them. One of their key activities is to work with news and information media to ensure appropriate coverage of the company's activities and products. Public relations specialists create publicity by arranging press conferences, contests, meetings, and other events that will draw attention to a company's products or services. Another public relations responsibility is crisis management—that is, handling situations in which public awareness of a particular issue may dramatically and negatively impact the company's ability to achieve its goals. For example, when it was discovered that some bottles of Perrier sparkling water might have been tainted by a harmful chemical, Source Perrier, SA's public relations team had to ensure that the general consuming public did not thereafter automatically associate Perrier with tainted water. Other public relations activities include lobbying, advising management about public issues, and planning community events.

Because public relations does not always seek to impact sales or profitability directly, it is sometimes seen as serving a function that is separate from marketing. However, some companies recognize that public relations can work in conjunction with other marketing activities to facilitate the exchange process directly and indirectly. These organizations have established marketing public relations departments to directly support corporate and product promotion and image management.

Public relations, in contrast to advertising and sales promotion, generally involves less commercialized modes of communication. Its primary purpose is to disseminate information and opinion to groups and individuals who have an actual or potential impact on a company's ability to achieve its objectives. In addition, public relations specialists are responsible for monitoring these individuals and groups and for maintaining good relationships with them. One of their key activities is to work with news and information media to ensure appropriate coverage of the company's activities and products. Public relations specialists create publicity by arranging press conferences, contests, meetings, and other events that will draw attention to a company's products or services. Another public relations responsibility is crisis management—that is, handling situations in which public awareness of a particular issue may dramatically and negatively impact the company's ability to achieve its goals. For example, when it was discovered that some bottles of Perrier sparkling water might have been tainted by a harmful chemical, Source Perrier, SA's public relations team had to ensure that the general consuming public did not thereafter automatically associate Perrier with tainted water. Other public relations activities include lobbying, advising management about public issues, and planning community events.

Because public relations does not always seek to impact sales or profitability directly, it is sometimes seen as serving a function that is separate from marketing. However, some companies recognize that public relations can work in conjunction with other marketing activities to facilitate the exchange process directly and indirectly. These organizations have established marketing public relations departments to directly support corporate and product promotion and image management.

Many producers do not sell products or services directly to consumers and instead use marketing intermediaries to execute an assortment of necessary functions to get the product to the final user. These intermediaries, such as middlemen (wholesalers, retailers, agents, and brokers), distributors, or financial intermediaries, typically enter into longer-term commitments with the producer and make up what is known as the marketing channel, or the channel of distribution. Manufacturers use raw materials to produce finished products, which in turn may be sent directly to the retailer, or, less often, to the consumer. However, as a general rule, finished goods flow from the manufacturer to one or more wholesalers before they reach the retailer and, finally, the consumer. Each party in the distribution channel usually acquires legal possession of goods during their physical transfer, but this is not always the case. For instance, in consignment selling, the producer retains full legal ownership even though the goods may be in the hands of the wholesaler or retailer—that is, until the merchandise reaches the final user or consumer.

Many producers do not sell products or services directly to consumers and instead use marketing intermediaries to execute an assortment of necessary functions to get the product to the final user. These intermediaries, such as middlemen (wholesalers, retailers, agents, and brokers), distributors, or financial intermediaries, typically enter into longer-term commitments with the producer and make up what is known as the marketing channel, or the channel of distribution. Manufacturers use raw materials to produce finished products, which in turn may be sent directly to the retailer, or, less often, to the consumer. However, as a general rule, finished goods flow from the manufacturer to one or more wholesalers before they reach the retailer and, finally, the consumer. Each party in the distribution channel usually acquires legal possession of goods during their physical transfer, but this is not always the case. For instance, in consignment selling, the producer retains full legal ownership even though the goods may be in the hands of the wholesaler or retailer—that is, until the merchandise reaches the final user or consumer.